Loss Aversion Biases

Human beings, like any other creature, seek pleasure and wish to avoid pain. However, our priority is to avoid pain because pain is far more powerful than pleasure. Imagine that you are perfectly healthy and all your body parts are working perfectly fine, except for one tooth, which has been painful for a while. Can you feel happy knowing that 99.9% of your body is healthy and working fine? You can’t because a single source of pain is more than enough to counter the joy of numerous sources.

According to behavioural economics, the “losses loom larger than gains” as the pain of losing something is much more than the pleasure of gaining the same thing. The resultant theory is often called “loss aversion”, which is an important concept associated with prospect theory, a behavioural model that shows how people decide between alternatives that involve risk and uncertainty, the likelihood of gains or losses.

Loss aversion is a popular concept. It has been estimated that the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel laureate of economics, explains that he encounters loss aversion regularly and that it is easy to observe. He offers the example of a coin-flip scenario. He asks his students, ”I’m going to toss a coin, and if it’s tails, you lose $10. How much would you have to gain on winning in order for this gamble to be acceptable to you?” He says that most people expect at least $20 for the winning outcome. That is twice as much upside as there is downside, as in flipping the coin, the chance of winning and losing is 50%. He also says that if you raise the amount to $10,000 in the question, people will respond with $20,000. Loss aversion is very much a consistent phenomenon regardless of the amounts involved. [1]

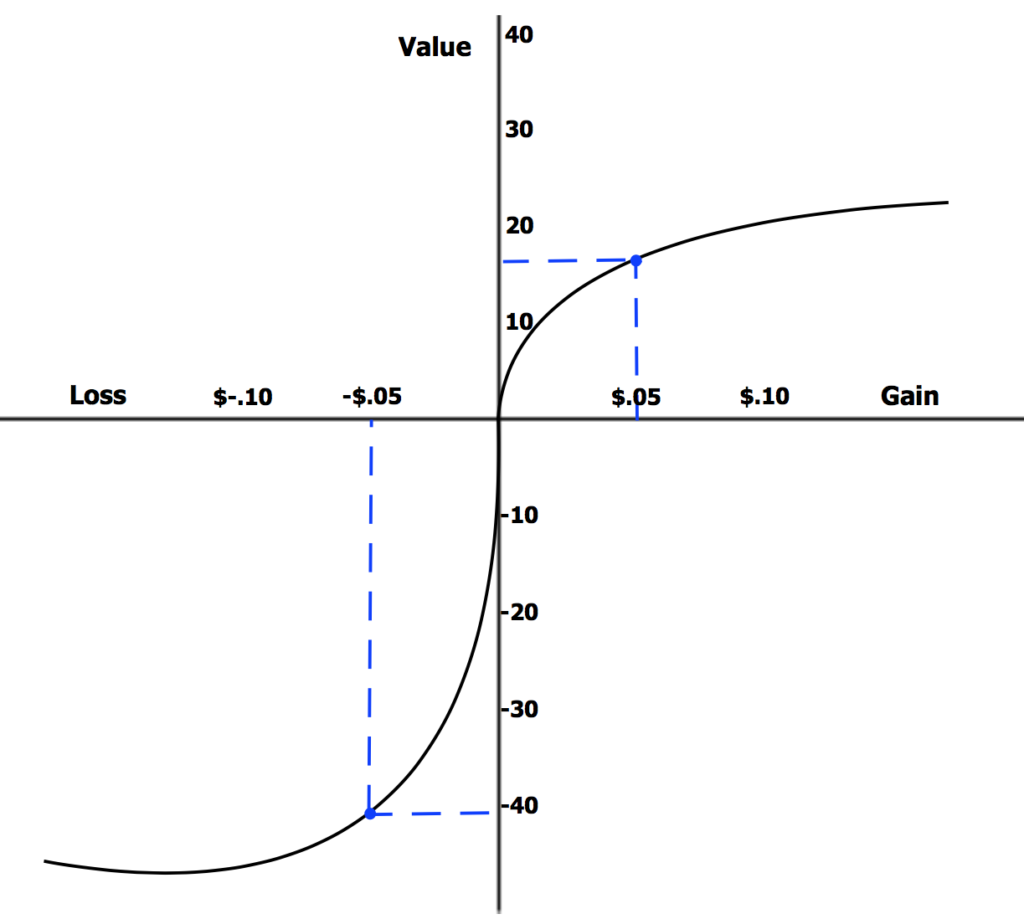

Loss aversion is considered to be one of the most powerful biases and is neatly represented in the form of the following graph. [2]

As evident in the above diagram, the pain of loss is twice as powerful as the pleasure of gain. The loss aversion phenomenon leads to different kinds of bias as follows.

(a) Endowment Effect

We value an entity not only based on its inherent value, which is objective and the same for all, but also due to our attachment to it, based on our feelings. We would not like to part with our children for any amount of money, or in exchange for any other child, however attractive they may be. The value of our children is far more for us than for any other person who has no emotional connection with the child. We develop attachments not only with our friends and family members, but even with our pets, and inanimate things like cars, houses or furniture.

We tend to place a greater value on things once we own them and become possessive about them. This is especially true for things that aren’t commonly bought or sold on the market, usually items with symbolic, experiential, or emotional significance. This type of bias is called “endowment Bias” or “endowment effect”.

The endowment effect refers to an emotional bias that causes individuals to value an owned object higher, often irrationally, than its market value. As a result, we are relatively reluctant to part with a good we own for its market value, the cash equivalent, or the amount that other people are willing to pay. This effect happens because we tend to place a higher value on an object that we already own than the value we would have placed on that same object if we did not own it. Once we own something, we often get emotionally attached to it, and then we don’t want to give it up, even if we are offered a higher price for it. So, most of the time, the market value of a good is lower than what we are willing to accept when selling it. Hence, we find it difficult to sell our goods and end up accumulating so much junk and portfolios in our homes due to our inability to dispose of them.

However, the endowment effect can sometimes work in opposite ways as well, when the ownership of something reduces its value rather than increasing it. We know that the grass is greener from the other side of the fence. Similarly, people often fail to appreciate what they have and appreciate more what they don’t have, and they may be ready to exchange them. Many people find other people’s spouses more attractive than their own, as with time, they may get bored of their spouse. Similarly, people also lose the charm of the job they desired so much in the past.

However, despite losing interest in the things people have, they feel reluctant to lose what they have to gain what they don’t have since the pain of losing what you have is more than the joy you expect to get from the new things.

(b) Sunk Cost Fallacy

The Sunk Cost Fallacy describes our tendency to follow through on an endeavour if we have already invested time, effort, or money into it, whether or not the current costs outweigh the benefits. For example, if you have already purchased a high price stock whose prices are going down consistently, and you have no reason to believe that the changearound would happen, still you don’t wish to sell that stock, because you don’t wish to accept that you have committed a mistake by buying the stock. Similarly, many students in India, who have already spent several years writing the civil services examination for the top government jobs in India, don’t quit, because they feel that they have already spent so many years for the examination, and they can’t allow all that effort to go to waste. In this way, they waste several more years in their quest for their dream job.

There are many reasons for irrational behaviour. One reason is that we are taught from early childhood to persevere and never give up. This behaviour is driven by a need for consistency. So, quitting midway and changing the path amounts to giving up, which makes us feel like cowards and losers. We are reminded of the famous quote of Vince Lombardi “Winners never quit and quitters never win.” We somehow believe that by being consistent, we will succeed one day.

Secondly, we wish to be consistent in our decision-making to build credibility. When we decide to change the decision midway, we create a contradiction because we admit that we were wrong earlier. Moreover, we can also not be absolutely sure, if the new decision would be the right one. Hence, we carry out our earlier project at least to look firm and consistent.

It is because of the sunk cost fallacy that many people continue with old relationships even though they know that they can never be happy with their partners. They often don’t quit the jobs they hate because they believe that they have invested so many years in the job.

The sunk cost fallacy is a vicious cycle because we continue to invest money, time and effort into the projects that we have already invested in. The more we invest, the more we feel committed to it, and the more resources we waste following through on our decision.

The main reason for the sunk cost fallacy is our tendency of loss aversion. When we sell our stock at a lower price, we immediately suffer the loss while keeping it with ourselves shows our portfolios better. We can avert this fallacy by focusing on the gains rather than the losses. So, think about the benefits you may reap and the losses you can avoid in future by making the right decision at the right time. We must also be humble to accept that we have made mistakes because to err is human. So learn the right lesson from the mistake and move ahead.

(c) Status Quo Bias

Many people are not happy with their jobs and they wish to change their jobs, follow their passion or do something which they love to do. However, most of them spend their lives doing the same salaried jobs. Someone has wisely said, “Your salary is the bribe they give you to forget your dreams”. I was an officer of the Indian Revenue Service for more than twenty-five years and I know that many of my colleagues were unhappy with their jobs. They felt trapped in their jobs and they saw their life slipping by every day. By the time they retire from their government job at the age of sixty, they would be too old to start something new. However, when they had the time, energy and resources, they preferred to live in their comfort zone maintaining the status quo in their lives.

The status quo bias is a form of cognitive bias where people prefer that things stay as they are or that the current state of affairs remains the same. A status quo bias is the result of the people’s resistance to change. By maintaining the status quo, people minimise the risks associated with change, but they also forgo the potential benefits that the change may ensue.

Status quo bias is also a manifestation of the loss aversion tendency of people. Whenever there is a change, there are some risks involved. However great the benefit may be, there is always some possibility of suffering the loss. Most people wish to avoid any loss by sticking to their comfort zone rather than giving themselves a new life by changing the status quo and getting out of their comfort zone.

(d) Wounded Ego Syndrome

Imagine that you are sitting under a tree in an open restaurant with a beautiful garden. You ordered your favourite drink, say milk-badam (almond milk). The waiter serves you the milk and you are just going to take a sip. Suddenly, a bird sitting over the tree poops and it falls in your milk. Can you still drink the milk? Can you ignore one drop of poop because there are millions of drops of almond milk in the glass?

The answer is no because that one drop of bird-shit would spoil millions of drops of milk. You will throw away the entire milk for that one drop of shit. The same principles hold good in the case of every intimate relationship. One action that deeply hurts your loved one can spoil years of your good work. A million apologies and good work can’t overcome one bad action ( like a single one-night stand) that hurts your heart. Your beloved would remember that one hurtful action deep much more than a million of your good deeds.

We have to be very careful when dealing with people since good and bad actions don’t weigh equally. The loss due to our wrong action may be much more, and sometimes even irreversible, than the gain due to good action which is usually cumulative. When our loved one’s ego is hurt, all our good deeds in the past are nullified. The key to maintaining a lifelong good relationship is, therefore, to overcome that one moment of anger that acts like poison to any relationship. One bad mistake can be like a matchstick that can destroy the beautiful house of love you have built with your sweat and blood over several years.

Overcome Loss Aversion Biases

We can overcome our tendency of loss aversion by correctly assessing the possibility of the gains. Suppose the odds of dying from road accidents is 0.01% in a year duration because 10 people die of road accidents for 100,000 of the population. However, this odd is not an inevitable thing as you can manage it to a much lower level by driving slowly, avoiding night driving on highways, not driving under the effect of alcohol, or driving less frequently and using air travel for longer distance travel etc. In the same way, the odds of heart attack may be 40/100,000, but you can manage it to a much lower level by maintaining the right lifestyle, avoiding tension, maintaining weight etc.

In the same way, in the civil services examination, 1000 aspirants get selected among one million applicants which puts the odds at 0.1% or 1/1000. However, such a mechanical calculation is misplaced because selection is not done purely random basis, in which case the odd would have been 0.1% for all. Since selection is based on merit and performance, depending on your level of preparation and your past performance, the odds can vary from 0% to nearly 100%. While we know that only 10% of startups succeed, the 10% success rate is not a divine or natural law, but an empirical reality. If your idea is good, you are creative, work harder and possess expertise in the field, your chances of success are much better than 10%. The same thing holds good for writers, singers, actors, etc. We have to assess the true odds of success ourselves instead of relying on empirical evidence.

We are not mere helpless instruments waiting our turn to be used by destiny, but active participants who decide our destiny. We can reduce the risk substantially by taking precautions and taking proactive steps to improve our chances of success and avoid failures.

References

[1] Interaction Design Foundation – IxDF. (2016, June 3). Loss Aversion Theory – The Economics of Design. Interaction Design Foundation – IxDF. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/loss-aversion-theory-the-economics-of-design [2] Loss Aversion, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_aversion