Structure of Arguments

A critical thinker must use reason and logic to make decisions instead of relying on emotions. Hence, logic is the essence of critical thinking. The word “logic” originates from the Greek word “logos”, which means reason, discourse, or language. Accordingly, logic is defined as the study of the laws of thought or correct reasoning. It is a system of reasoning that aims to draw valid conclusions based on given information.

Logic consists of arguments. However, an argument in logic does not mean an angry discussion between two or more people who disagree with each other. Instead, in logic, an argument means the reasons we give to support our opinion about something. An argument is thus a claim that something is true, while logic means the rules and methods for evaluating arguments, ensuring they are sound and convincing.

Functions of Arguments

Arguments are the most potent tool of critical thinkers, with functions. The most essential functions of the arguments are as follows.

- Critical Evaluation: We get a lot of information, ideas, and opinions from multiple sources daily. Some of them are true, but most of them are false. Unfortunately, fake news or false information spreads much faster and often goes viral because these are designed to please people and validate their false opinions. On the contrary, the truth is often bitter, which most people don’t wish to hear. Hence, truths are hardly popular. Arguments are useful in critically evaluating information, ideas and opinions to help us differentiate fact from fiction and truth from falsehood.

- Decision-Making: We have to make numerous decisions in our lives. Some are routine in nature, whereas others are critical to shaping our lives. Decision-making involves exploring multiple options and then choosing the best options among them. Most people make decisions based on gut feeling, intuition or emotions without critically analysing their options. Arguments help us evaluate each option rationally, understand the pros and cons of each decision objectively and hence facilitate informed decision-making.

- Problem-Solving: We face numerous challenges in our personal and professional lives. We are trained to solve textbook problems in our schools and colleges after every lesson is learned, particularly in mathematics and science subjects, using the steps and formulas discovered by mathematicians and scientists for thousands of years. However, hardly any school course curriculum helps us solve real-life problems. Arguments can help us identify the conflicts, disputes, or problems in our lives accurately and objectively and resolve them.

- Persuasion: While in schools and college, we can achieve excellent results solely due to our own efforts, to succeed in the real world, we need teamwork and leadership qualities. One of the most essential qualities of a leader is to convince others to accept their point of view so that all the team members voluntarily follow the same goal. Former American president Dwight D. Eisenhower explained the virtue of persuasion in leadership, “I would rather try to persuade a man to go along because once I have persuaded him, he will stick. If I scare him, he will stay just as long as he is scared, and then he is gone.” Arguments are the most powerful tool to convince others of a particular viewpoint or position and thus align their thoughts in the same direction as that of the speaker.

- Personal Growth: Arguments stimulate analysis, evaluation, and reasoning and thus lead to our intellectual development. Critical thinkers use arguments with appropriate reason and logic to express their thoughts instead of using emotions, which are subjective and vary from person to person. When we use arguments as a tool to convince others, we are also willing to be persuaded by others when we find their arguments convincing. When we wish to persuade others, we must understand the thoughts and feelings of other people, which helps us develop empathy and compassion for another person. As a result, we improved our communication skills as we used the most appropriate argument to convince our audience. Hence, arguments are useful in developing our personality by making us more confident, assertive and persuasive.

Structure of Argument

A good argument attempts to convince the audience about the speaker’s idea, message or point of view. A conclusion is thus the message which the author wishes the audience to accept or believe. We all wish others to believe what we think or believe to be right. However, the difference between an ordinary message and a message communicated through argument is due to the difference in reason. In an argument, the conclusion is supported by other statements, which are often called premises, that provide the reason to support the conclusion. Hence, the writer does not want to accept his conclusion because he says it, but he wants you to accept the message because of the reasons he provides. Hence, an argument typically has the following form.

- X (Conclusion) because of Y (premises containing reasons).

Thus, a conclusion in an argument is inferred based on the premises, which provides the reason for accepting the conclusion. If no supporting reasons are given in the conclusion, it is not an argument but merely an opinion of the person.

For instance, consider a popular saying, “Honesty is the best policy”. This is an explicit statement expressing the opinion of the speaker without providing any statement containing the reason why the audience should accept honesty as the best policy. However, if we add reasons, it becomes an argument. Hence, the argument can be expressed as,

- Argument: Honesty is the best policy BECAUSE it gives you peace of mind.

The above statement can be said to be an argument because the conclusion is based on the premises, which contain the reason to believe or accept the conclusion. However, the argument is still not complete unless it is assumed that peace of mind makes honesty the best policy. Hence, the complete argument can be written as,

- Every human being wants peace of mind. (Assumed premises)

- Honesty gives you peace of mind. (Given premises)

- Hence, honesty is the best policy. (Conclusion)

Since the conclusion is based on the strength of the premises, the quality of the premises determines the quality of the conclusion. If the premise “Every human being wants peace of mind. “ is again an explicit statement given without any proof. There is no data or research to support the claim that every human being wants peace. Hence, if the premises are not reliable, the conclusion is undependable. For instance, in this case, the premise if most people don’t consider peace of mind as the most important goal of life, and instead want wealth, power or fame in their life, then the assumed premise is incorrect and hence the conclusion is also wrong.

The strength of the conclusion comes from the strength of the premises. Accordingly, the power of the conclusion can’t exceed the power of the premises. Hence, to make your argument more persuasive, you must support her beliefs with strong reasons. In every society, some statements are taken for granted because most people accept them as true. Hence, a speaker often uses such a statement to prove his conclusion. For example, if the audience primarily consists of believers, the following argument would be more persuasive.

- Argument: Honesty is the best policy BECAUSE God said in the Holy Book that honest people will go to heaven while the dishonest will be thrown to hell.

Now, if the audience has faith in their Scripture, these arguments are far more persuasive than those that cite “peace of mind” as the reason to be honest. However, the same argument will have little or no effect on an atheist since he does not believe in God or the Scriptures. According to the Bible, Jesus Christ asked people to give charity and serve the people because serving the people is like serving God. In the parable of the king, the king says that those who gave food, drink, clothing, care, and visited to the poor will inherit the kingdom. (Matthew 25:34-36)

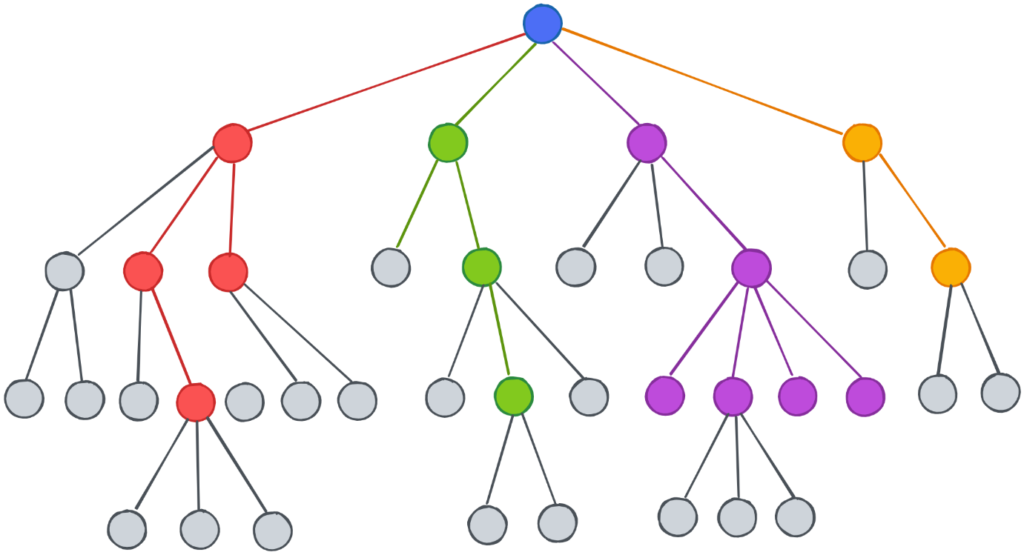

The conclusion in an argument is thus built on the conclusions contained in the premises of the arguments, which are again based on the conclusion derived from some other arguments, and this continues till we reach the irrefutable facts. The following story interestingly explains this.

A well-known scientist once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the Earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the centre of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy.

At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: “What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant turtle.”

The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, “What is the turtle standing on?”

“You’re very clever, young man, very clever,” said the old lady. “But it’s turtles all the way down!”

While this story may look funny, this is what our ancestors believed for hundreds of thousands of years. Only when the scientists went deep into the issue and found facts did the new concept of the universe be discovered. The relationship between the conclusion and premises can be shown in the form of the following decision tree.

Most people don’t dwell so deeply into the argument and accept the premises as true. However, it is important to understand that the strength of the conclusion can never be higher than that of the premises, whose strength is again based on the premises on which it is based. Only observable facts are beyond doubt and may be said to contain absolute truth. For instance, the mathematical assertions (2+2=4), scientific laws (law o’f gravity), or matters of observable facts (All humans are mortal) have been tested by numerous people and always found to be true are the solid premises, whose truth is indisputable. Hence, if our arguments are based on them, they have the highest persuasive power. Hence, the shortest is the chain reaching the facts; the strongest is the persuasive power of the argument.

We can use different reasons to convince the audience to accept our viewpoint or idea. Some reasons may be in the form of statements which are widely believed by people as true, e.g. “Nothing moves without the will of God”, “Honesty is the best policy”, “You shall reap what you sow”, etc. These statements depend on the kind of issue and the audience we are addressing. However, all such statements cater only to a particular audience and won’t have a universal appeal. For instance, you can easily convince a Muslim not to drink alcohol or a Hindu not to eat cow meat, citing the passages from the relevant scriptures, but the words of scripture shall have no effect on atheists or people of other religions.

Most people in the modern world have a much deeper trust in scientific investigations, which cut across all religions, races or nationalities. Hence, if the premises are based on facts, scientific studies, statistics, and expert opinions, they can be accepted by most rational people. Likewise, when the speaker provides well-known anecdotes of great people whom people widely respect, they can easily accept the premise as true. When the speaker is well known and trusted by the audience, their personal experiences are easily believed by the people as true. Often, the arguments consist of metaphors, analogies, fables and stories, which can communicate complex ideas in a simple way to convince the audience.

People don’t easily give up their existing ideas, beliefs, and faiths, no matter how strong an argument may be. They often find a way to counter the argument and remain loyal to their existing beliefs. To cultivate a new idea in the audience’s mind, we must counter (existing) logic with (new) logic, evidence by evidence, studies by studies, facts by facts, stories by stories and metaphors by metaphors. For instance, if you want to convince a Hindu to discard idol worship, it is easier to convince him using another Hindu Scripture, i.e. Vedas, instead of telling them that there is no God. Likewise, suppose you want to change the eating habits of a rational person whose diet is based on a scientific study. In that case, you present another scientific study with an equal or more reliable source to convince him.

However, it is not easy to change people’s beliefs because their beliefs are the foundation of their thoughts. Hence, when a speaker tries to convince the audience by using evidence or reason that contradicts his beliefs, the person resists because to accept the new reason, he has to discard his old belief, which is the foundation of all his reasons. We have an emotional attachment to our beliefs and a sense of loyalty towards them since they are part of us, our beings. Getting rid of a belief is no less painful than severing a part of our body. Moreover, our beliefs connect us with our loved ones, our friends and family and the members of society. Losing a belief that connects us to the people close to us can isolate us from them and cause tremendous emotional pain. Hence, most people resist accepting a reason or evidence that challenges their existing belief and seek to demolish it. For instance, if your argument is based on the premise that there is no God and everything happens due to a matter of chance, it is difficult to convince the idea to a person who has deep faith in God and believes that not a leaf moves without the will of God.